Where is the Mass Air Flow Sensor Located? A Truck Owner’s Full Guide

The Mass Air Flow (MAF) sensor is a small component that plays a critical role in the performance, efficiency, and drivability of your truck’s engine. When it works, your engine runs smoothly. When it gets dirty or fails, it can cause a cascade of frustrating problems, from a rough idle to poor fuel economy.

This guide serves as a definitive resource for truck owners. It will not only show you precisely where the MAF sensor is located but also help you understand what it does, how to diagnose it if it’s failing, how to service it yourself, and how to avoid costly, unnecessary repairs.

Mass Air Flow Sensor Location (The Quick Answer)

This section provides the direct answer to help you find the sensor quickly.

The 30-Second Answer: The mass air flow sensor is almost always located in the engine’s air intake duct, positioned between the air filter box and the throttle body.

How to Find It on Your Truck:

- Open the hood and locate the large plastic box that holds your engine’s air filter (the air filter housing).

- Follow the large-diameter plastic or rubber intake tube that runs from the air filter box toward the engine.

- Look for a small, typically cylindrical component inserted directly into this tube. You will see an electrical connector with a wiring harness plugged into it.

- On many GM trucks (like the Silverado, Sierra, or Tahoe), the MAF sensor is on the passenger side of the engine and is often secured by two T25 Torx screws.

- On a diesel truck (like a Duramax), the location is similar: between the air filter box and the inlet of the turbocharger.

The location of the MAF sensor is a critical engineering decision. It is placed after the air filter because its primary function is to protect the sensor’s delicate internal components. The sensor uses a very sensitive “hot-wire” that can be easily damaged or contaminated by dust, oil, or debris. The air filter acts as a barrier to keep the sensor clean. Its position before the throttle body is also essential, as it must measure the total mass of air available to the engine before the throttle plate opens to control how much of that air is allowed in.

The Ins and Outs of Your Mass Air Flow Sensor

A visual guide to finding, understanding, and troubleshooting this critical component.

Why Does the MAF Sensor Matter?

The Mass Air Flow (MAF) sensor is a vital part of your truck’s engine management system. Its one and only job is to measure the exact amount (mass) of air entering the engine. This data is sent to the engine control unit (ECU), which then calculates the perfect amount of fuel to inject for optimal combustion. A clean, accurate MAF sensor is the key to a smooth-running engine, good fuel economy, and passing emissions tests.

Finding Your MAF Sensor: A Typical Layout

You don’t have to be a master mechanic to find the MAF sensor. It’s almost always located in the air intake duct, right after the air filter box and before the throttle body. Follow the path the air takes into your engine, and you’ll find it. Look for a small, cylindrical component with an electrical wiring harness plugged into it.

Common Symptoms of a Failing MAF

When the MAF sensor gets dirty or fails, it sends incorrect air readings to the ECU. This throws off the air-fuel mixture, leading to a variety of noticeable problems. The Check Engine Light is the most common indicator, but poor performance and rough idling are also strong signs.

MAF vs. MAP: What’s the Difference?

It’s easy to confuse the MAF (Mass Air Flow) sensor with the MAP (Manifold Absolute Pressure) sensor. While both help determine fuel injection, they measure different things. The MAF measures air *mass* (volume/density), while the MAP measures *pressure* in the intake manifold. Some engines use one or the other, and many modern engines use both for greater accuracy.

| Feature | MAF Sensor | MAP Sensor |

|---|---|---|

| Full Name | Mass Air Flow | Manifold Absolute Pressure |

| What it Measures | Mass of air entering engine | Engine vacuum/pressure |

| Typical Location | In the air intake tube | On the intake manifold |

| Primary Use | Calculate fuel injection | Calculate engine load |

DIY Fix: Cleaning vs. Replacing Costs

The good news? A faulty MAF sensor doesn’t always mean an expensive repair. Often, the sensor is just dirty from oil vapors and dust. A $15 can of specialized MAF sensor cleaner and 20 minutes of your time can restore it to perfect working order, saving you hundreds over a shop replacement.

What is a Mass Air Flow (MAF) Sensor and Why Does Your Truck Need It?

To diagnose the sensor, it’s essential to understand its function. The MAF sensor’s job is to provide the Engine Control Unit (ECU) or Powertrain Control Module (PCM) with a real-time, precise measurement of the exact mass of air entering the engine.

This brings up a key question: why measure mass and not just volume? Air density is not constant; it changes dramatically with altitude, air temperature, and humidity. A cubic foot of cold, dense air at sea level contains significantly more oxygen (mass) than a cubic foot of thin, hot air in the mountains. The ECU needs to know the exact mass of oxygen to inject the precise mass of fuel for optimal combustion.

The MAF sensor is the modern, digital solution to a problem that used to require manual adjustment. In older, carbureted engines, a driver would need to manually adjust the air-fuel mixture to prevent the engine from running poorly at high altitudes. The MAF sensor, working with the ECU, performs this adjustment millions of times per second.

Most modern trucks use a “hot-wire” or “hot-film” type MAF sensor. Here is how it works:

- Inside the sensor housing are two small wires.

- One wire is a heated element, which an electrical current keeps at a precise temperature (e.g., 75-100°C) above the second wire, which measures the ambient temperature of the incoming air.

- As air mass flows across the hot wire, it cools it down.

- The sensor’s electronic circuitry instantly increases the electrical current to the hot wire to maintain its constant target temperature.

- The amount of current required to keep the wire hot is directly proportional to the mass of the air flowing past it.

- This current reading is converted into a voltage or digital frequency signal and sent to the ECU. The ECU then uses this data to calculate the exact amount of fuel to inject.

Description: A simple, clean line-art diagram titled ‘The Air Intake Path.’ It will show a flow:

- Ambient Air ->

- Air Filter Box ->

- MAF Sensor (in intake tube) ->

- Turbocharger (if applicable) ->

- Throttle Body ->

- Intake Manifold ->

- Engine

This precise measurement of engine load has implications beyond just the air-fuel ratio. The PCM also uses the airflow data to help determine the shift points for the automatic transmission. If a MAF sensor is dirty and under-reporting airflow, the ECU will believe the engine load is low. This can cause the transmission to shift into a higher gear too early, bogging down the engine and making the truck feel “lazy” or unresponsive. A truck owner might mistakenly believe they have a serious transmission problem when the real issue is a dirty sensor providing bad data to the computer.

5 Symptoms of a Bad or Dirty MAF Sensor in Your Truck

The symptoms of a failing MAF sensor are not random. They are the direct result of the ECU commanding the wrong air-fuel mixture because it is receiving bad data. A MAF sensor typically fails in one of two ways: it under-reports airflow (running the engine too lean) or it over-reports airflow (running the engine too rich).

Symptom 1: Check Engine Light (CEL) is On

This is often the first and most obvious warning. The ECU is sophisticated enough to know that the signal it’s receiving from the MAF sensor is outside of its expected parameters or is illogical compared to other sensor readings (like the throttle position and RPM). If your Check Engine Light is on, the first step is to retrieve the Diagnostic Trouble Codes (DTCs).

Symptoms of a Lean Mixture (Sensor is Under-Reporting Air)

This is the most common failure mode. Over time, dirt, dust, and oil vapors can coat the hot wire. This coating acts as an insulator, preventing the airflow from cooling the wire effectively. The sensor, therefore, “reads” less air than is actually entering the engine, causing the ECU to inject too little fuel.

- 2. Hesitation, Jerking, or Stalling: Your truck hesitates, jerks, or stumbles when you press the accelerator. This is because the engine is receiving too little fuel for the actual amount of air, causing a lean misfire.

- 3. Rough or Unstable Idle: The engine idles erratically, shakes, or the RPMs may hunt up and down. The ECU is struggling to maintain a stable combustion mixture at low RPMs and may even let the engine stall at a stoplight.

- 4. Difficulty Starting: The engine cranks for a long time or fails to start, particularly when the engine is cold. The initial lean fuel mixture is not rich enough to ignite properly.

Symptoms of a Rich Mixture (Sensor is Over-Reporting Air)

This is less common and is often the result of an electrical fault within the sensor itself. The sensor tells the ECU there is more air than there actually is.

- 5. Poor Fuel Economy: Your truck’s fuel consumption suddenly increases. The ECU is injecting more fuel than the engine needs, and the unburnt excess is wasted.

- 6. Black Smoke from Exhaust: This is the most telling sign of a rich condition. The black smoke is raw, unburnt fuel being “kicked out of the exhaust”.

Decoding Your Check Engine Light: Common MAF Sensor DTCs

If your Check Engine Light is on, a scan tool will retrieve a DTC. The most common codes specific to the MAF sensor range from P0100 to P0104.24

However, a faulty MAF sensor can also cause other codes to appear, which can lead to a misdiagnosis. A prime example is a P0171 (“System Too Lean”) or P0174 (“System Too Lean, Bank 2”) code. A technician or DIYer might see this code and blame a bad oxygen (O2) sensor. But the O2 sensor may be working perfectly; it is simply reporting the lean condition that the dirty MAF sensor created by under-reporting air. Replacing the O2 sensor in this case will not fix the problem.

This table details the most common MAF-related codes and their likely causes.

| DTC Code | Code Name | What It Means for Your Truck | Common Causes |

| P0101 | “Mass Air Flow (MAF) Circuit Range/Performance” | The sensor’s reading is illogical. It doesn’t match what the ECU expects to see based on RPM and throttle position. | Most common cause is a vacuum leak (un-metered air) after the sensor. Also, a very dirty sensor or clogged air filter. |

| P0102 | “Mass Air Flow (MAF) Circuit Low” | The sensor is reporting very low or zero airflow. | The sensor is likely dirty, faulty, or unplugged. Can also be a clogged air filter or a wiring issue. |

| P0103 | “Mass Air Flow (MAF) Circuit High” | The sensor is reporting an impossibly high amount of airflow. | Usually an electrical fault, like a short in the wiring, or a bad sensor. |

| P0100 | “Mass Air Flow (MAF) Circuit Malfunction” | A generic code indicating an electrical fault in the sensor circuit. | Damaged wiring, bad sensor, or PCM fault. |

| P0171 / P0174 | “System Too Lean (Bank 1 / Bank 2)” | The O2 sensor detects too much air (or not enough fuel). | Often a symptom of a dirty MAF sensor that is under-reporting air, or a vacuum leak. |

How to Service a MAF Sensor: Clean, Test, or Replace?

Given that most MAF sensor issues stem from a dirty element, cleaning is almost always the best, cheapest, and easiest first step.

A DIY Guide: How to Safely Clean Your MAF Sensor

This is a simple 15-minute job that can save you hundreds of dollars.

- Park and Cool: Park the truck on a level surface and ensure the engine is completely cool.

- Disconnect the Battery: Disconnect the negative battery terminal. This prevents any electrical short circuits and also helps reset the ECU’s fuel trim adaptations.

- Locate and Unplug: Find the MAF sensor in the intake tube and carefully disconnect the electrical wiring harness. There is typically a small release tab you must press.

- Remove the Sensor: Using the correct tool (often a T25 Torx bit for GM trucks or a Phillips screwdriver), remove the screws holding the sensor in its housing. Gently twist and pull the sensor straight out.

- CRITICAL: Use the Right Cleaner. You must use a cleaner specifically labeled “Mass Air Flow Sensor Cleaner”. This is a special, non-chlorinated solvent that is safe for plastics and electronics and evaporates completely, leaving zero residue.

- DO NOT USE: Brake cleaner, carburetor cleaner, throttle body cleaner, or any other aggressive solvent. These chemicals will melt the plastic housing and destroy the sensitive wires, guaranteeing you will have to buy a new sensor.

- DO NOT use compressed air, as it can damage the delicate wires.

- DO NOT touch the wires with a brush, cotton swab, or your fingers.

- Clean the Sensor:

- Place the sensor on a clean, dry towel.

- Liberally spray the cleaner (10 to 15 blasts) directly onto the sensor element, focusing on the small hot wires and plates visible inside the sensor’s port.

- Let it Dry Completely: This step is crucial. Let the sensor air-dry on the towel for at least 10-15 minutes. It must be 100% dry before reinstallation. Do not attempt to wipe it or speed up the process.

- Reinstall: Carefully insert the dry sensor back into the intake tube. Secure it with the screws (snugly, but do not overtighten) 5 and firmly reconnect the wiring harness.

- Reconnect Battery: Reconnect the negative battery terminal. Start the engine. The Check Engine Light should be off. If it remains, you may need to clear the codes with a scan tool.

A dirty MAF sensor is often a sign of another issue. While you’re at it, check your engine’s air filter to see if it’s clogged, damaged, or poorly fitted, which may be allowing contaminants to pass through.

How to Test a MAF Sensor with a Multimeter

If cleaning the sensor doesn’t fix the problem, the sensor itself may have failed electrically. You can confirm this with a multimeter before buying a new part.

A healthy sensor’s signal will rise smoothly with engine RPM. A bad sensor will be erratic. Data from a dying sensor often shows “flat lines” (no signal change) or impossible readings like “dips well below idle,” which a multimeter can detect as voltage drops.

Step-by-Step Test (General Guide):

- Reconnect the MAF sensor.

- Set your multimeter to DC Volts.

- Test 1 (Power): With the key ON but the engine OFF, back-probe the 12V power wire on the sensor’s connector (you may need a wiring diagram for your specific truck). Connect the black lead to the battery’s negative terminal. You should see ~12 volts. If not, you have a wiring problem, not a sensor problem.

- Test 2 (Ground): Perform a similar test on the ground circuit.

- Test 3 (Signal): Start the engine. At idle, back-probe the signal wire. You should see a low, stable voltage (typically ~0.5-1.0 volts).

- Test 4 (Dynamic Response): Have a helper slowly and smoothly rev the engine. As the RPMs increase, the voltage on your multimeter should rise smoothly and proportionally. If the voltage spikes, drops to zero, or “flat-lines” (doesn’t change) while the RPMs are climbing, the sensor is bad and must be replaced.

Average MAF Sensor Replacement Cost: DIY vs. Pro

If your sensor is confirmed to be bad, the cost to replace it varies wildly.

- The DIY Option: You can buy a new, high-quality MAF sensor for anywhere from $75 to $170, depending on your truck model. The replacement process is identical to the cleaning steps and takes about 15 minutes.

- The Professional Option:

- Independent Shop: Expect a total cost of $260 to $470. This typically includes $200-$330 for the part and $50-$170 for labor.

- Dealership: Be cautious. Costs can be significantly higher. For example, one real-world quote for a Nissan Rogue was $876. The breakdown was $294 for the part and $390 for labor—a labor rate 4-5 times higher than an independent shop’s estimate. This quote also included a $200 “fuel induction service” that the service writer admitted was “not totally necessary”. Always ask for an itemized quote and decline add-on services that are not required.

| Service Type | Estimated Part Cost | Estimated Labor Cost | Total Estimated Cost |

| DIY Cleaning | ~$15 (Cost of cleaner) | $0 | ~$15 |

| DIY Replacement | $75 – $170 | $0 | $75 – $170 |

| Independent Shop | $200 – $330 [43] | $50 – $170 | $250 – $470 |

| Dealership (Potential) | $290+ | $390+ | $680 – $900+ |

Advanced Truck Knowledge: MAF, MAP, Diesels, & Aftermarket Filters

This section addresses the more nuanced, high-level questions that are specific to modern trucks.

MAF Sensor vs. MAP Sensor: What’s the Difference?

This is a common point of confusion, especially with modern turbocharged engines.

- MAF (Mass Air Flow): Directly measures the mass of air flowing into the engine.

- MAP (Manifold Absolute Pressure): Indirectly calculates air mass by measuring the pressure (or vacuum) inside the intake manifold.

- Speed-Density Systems: Some trucks, like the 2016 Ford F-150 3.5L EcoBoost, do not have a MAF sensor. Instead, they use a MAP sensor along with RPM and air temperature data to calculate the air mass. This is known as a “speed-density” system.

Why would a truck manufacturer choose one over the other? MAP sensors are often considered more durable and reliable in the harsh, dusty, or high-vibration conditions that a truck or off-road vehicle might face. A MAP sensor is also well-suited for a turbocharged engine (like an EcoBoost) because it can read the positive boost pressure in the manifold. A MAF sensor is generally more precise, which is why it is preferred for meeting strict emissions targets. To get the best of both worlds, many modern trucks (including diesels) use both a MAF and a MAP sensor.

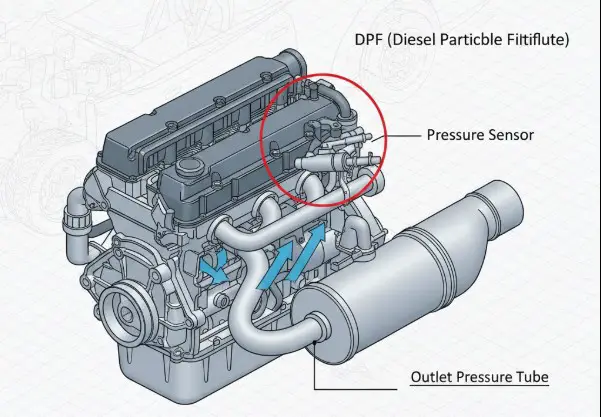

Do Diesel Engines Have MAF Sensors? (The Answer for Duramax, Powerstroke, & Cummins)

Yes. Almost all modern light-duty diesel trucks (Duramax, Powerstroke, etc.) are equipped with a MAF sensor.

Its location is just as you’d expect: between the air filter box and the turbocharger inlet.

However, the MAF sensor’s primary job on a diesel is different and even more critical. In a diesel engine, the MAF sensor is the key component used to calculate Exhaust Gas Recirculation (EGR) loads.

Here is how that works:

- The MAF sensor measures the total mass of fresh air entering the engine.

- The ECU already knows the engine’s displacement and RPM, so it can calculate the total volume of air the engine should be inhaling.

- By subtracting the measured fresh air (from the MAF) from the expected total air, the ECU can determine the exact mass of exhaust gas that is being supplied by the EGR system.

This has a huge implication for performance: if the MAF sensor on your diesel is dirty and under-reporting fresh air, the ECU will incorrectly believe the engine is receiving too much EGR (or that engine load is very low). To compensate and control emissions, the ECU will “de-fuel” the engine. This results in a “lazy truck,” “no response,” and a feeling that the engine “won’t fuel”. This low-power condition is a classic symptom of a dirty MAF sensor on a modern diesel.

The Great Debate: Do Oiled Air Filters (like K&N) Really Damage MAF Sensors?

This is one of the biggest controversies in the truck community.

- The Accusation: Many mechanics and dealers claim that the oil from aftermarket “high-performance” filters (like K&N) can “weep” off the filter media, get sucked into the intake, and coat the hot wire of the MAF sensor, causing it to fail.8

- The Defense: K&N and other manufacturers state this is a “myth”. They argue that the amount of oil used is minuscule (less than two ounces) and is fully absorbed by the cotton filter media. Their own testing, which included submerging a functional MAF sensor in filter oil, showed no damage or performance loss. They contend that failures are caused by (a) dirt that got through a competitor’s filter or (b) user error.

The evidence from both sides points to a single, logical conclusion: the problem is not the filter itself, but the maintenance. A brand-new, properly oiled filter from the factory is likely fine. The real risk comes from a user who, after cleaning the filter, over-oils it. This excess oil is not absorbed and can then be pulled by the engine’s vacuum onto the MAF sensor’s hot wire, causing contamination.

Expert Recommendation: If you use an oiled, reusable filter, you must be extremely careful during the re-oiling process. Follow the manufacturer’s instructions precisely. For most truck owners who value long-term reliability over a negligible performance gain, a high-quality, dry disposable paper filter is the safest and most maintenance-free option for protecting your MAF sensor.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: Can you drive with a bad mass air flow sensor?

A: Yes, but it is not recommended. When the ECU detects a complete failure, it will ignore the sensor and enter a “limp mode”. It will use pre-programmed default tables (a “speed-density” backup) to guess the air-fuel mixture. This will allow the engine to run, but you will experience very poor performance, sluggish acceleration, terrible fuel economy, and potential stalling.

Q: Is it better to clean or replace a MAF sensor?

A: Always try cleaning it first. A can of MAF sensor cleaner costs about $15, and the job takes 15 minutes. In the vast majority of cases, the sensor is simply dirty, not broken. If cleaning does not fix the symptoms or the DTC code, then it is time to replace it.

Q: What is the most common sign of a bad MAF sensor?

A: The most common sign is the Check Engine Light. The most common drivability symptoms are engine hesitation or jerking during acceleration 19 and a rough, unstable idle.

Q: How much does it cost to fix a mass air flow sensor?

A: DIY cleaning costs about $15. A DIY replacement costs $75 – $170 for the part. A professional replacement at an independent shop typically costs between $250 and $470.

Q: What’s the difference between a MAF sensor and a MAP sensor?

A: A MAF (Mass Air Flow) sensor directly measures the mass of air flowing into the engine. A MAP (Manifold Absolute Pressure) sensor indirectly calculates air mass by measuring pressure in the intake manifold. Your truck may have one, the other (like some EcoBoost F-150s 2), or, in many modern cases, both.